The

Hamilton Inquiry.

The

Hamilton Inquiry.

(Now the

Barron Inquiry.)

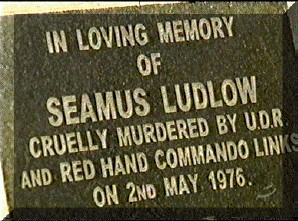

The

private Barron Inquiry report into the murder of Seamus Ludlow was published

with much fanfare in Dublin on 3 November 2005.

The

four chief loyalist Red Hand Commando/UDR suspects have been publicly identified

for the first time - their names appearing not only in the published 100-page

report but also extensively in press reports thereafter. For further

inforemation on this important development go here.>>>

The Ludlow family

had campaigned consistently for

public inquiries in both jurisdictions in Ireland into the sectarian murder in

County Louth of their dear relative Seamus Ludlow. Thus, initially, the

Ludlow family did not accept the private inquiry announced by the Dublin

government.

Seamus,

as it is now widely known, was murdered by members of the outlawed

Loyalist murder gang, the Red Hand Commando and the British Army's Ulster

Defence Regiment (UDR) on the

night of 1st and 2nd May, 1976.

The four suspects, whose names

were all known to

the Ludlow family for several years, were arrested by the Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC) in February 1998, but once again

they evaded the justice that they were protected from since 1976.

The Ludlow family demands a full accounting of

the failure by both the Gardai and the RUC to bring the killers to justice. They

demand explanations and apologies for the smearing of the innocent victim and

the covering-up of his murder to protect his killers who were identified very

soon after the crime was committed.

The Irish government

hoped that the

Ludlow family would accept the ongoing private Hamilton Inquiry (conducted since

October 2000 by the former Irish Supreme Court judge Henry Barron), into the Dublin,

Monaghan and Dundalk bombings, something less than the public inquiry that

had

been demanded, but this private option was been rejected at the outset.

The

then Irish Minister for Justice, Mr. John

O'Donoghue, formally recommended the private Barron Inquiry with a follow-up

public Joint Oirachtas Committee hearing, to the Ludlow family, when they met

him in Dublin on 23 May 2001. The Ludlow family rejected his proposals outright.

They could have no confidence in any inquiry held in private, where there is no

public access to witness evidence or documents. Mr. O'Donoghue then took the

view that there was nothing further to discuss and that it was the Ludlow family

who were the cause of the stalemate! He then abruptly walked out of the

meeting!

The

Ludlow family rejected this view entirely, seeing very little in the

Minister's proposals that could establish truth and justice for Seamus

Ludlow. The Ludlow family saw the failure to achieve any movement resting with the Irish government,

which makes regular demands of the British to hold public inquiries into

other ghastly state killings in the North of Ireland, while it hypocritically refuses to hold

public inquiries in its own jurisdiction.

Indeed,

they Ludlow family were outright in their condemnation of the Minister's private

inquiry option and they ridiculed his proposal for a Joint Oireachtas Committee

hearing, since that body was now looking weaker by the day as its powers to ask

questions and summon witnesses were daily being eroded by challenges from the

gardai and Mr. O'Donoghue's own department since it began its investigation of

the gardai armed Emergency Response Unit (ERU) and its shooting dead of John Carthy at

Abbeylara, County Longford.

The only obstacle to the holding of an inquiry

into Seamus Ludlow's foul murder and the cover-up, or more precisely the

publication of any report of such an inquiry, as indicated in his official report by the

Irish Victims Commissioner John

Wilson - a report commissioned and accepted by the Dublin government - was the

then apparently strong possibility of a

pending prosecution of the four Loyalist suspects in the North.

This possibility has

been removed by the failure of the Northern Ireland Director of Public

Prosecutions (DPP) to bring charges against any of the former UDR/Red Hand

Commando suspects. Accordingly

the Ludlow family now reaffirmed its demand for a fully public and independent inquiry to be convened at the

earliest possible opportunity.

This possibility has

been removed by the failure of the Northern Ireland Director of Public

Prosecutions (DPP) to bring charges against any of the former UDR/Red Hand

Commando suspects. Accordingly

the Ludlow family now reaffirmed its demand for a fully public and independent inquiry to be convened at the

earliest possible opportunity.

Given the shameful failure of the

Northern Ireland DPP, and the RUC, to press charges against any of the suspects,

there could, in the Ludlow family's view, be no justification for a private

inquiry as recommended by Mr. Wilson.

Further, Mr. Hamilton's shock resignation

in October 2000, on health grounds, from his private inquiry, prior to his

completing his report on the Dublin and Monaghan bombings (which left 34 people

dead and 300 injured in the four separate no-warning bombs, planted by the UVF at

the height of the Loyalist Ulster Workers Council strike against the Sunningdale

Agreement in 1974), raised serious questions about the suitability of a

one-man private investigation of such grave issues. Sadly, Mr. Hamilton was very

ill indeed, for his death was reported in the national press on 1 December 2000.

To date, neither the RUC nor the Gardai have

issued an apology for their role in protecting Seamus Ludlow's killers and the

British authorities in Belfast and their Irish counterparts in Dublin have not

responded to the Ludlow family's just demands for a full and independent public inquiry.

While the

British remain utterly silent on this issue, in Dublin there remains a fierce

reluctance to go beyond a private inquiry, like the Hamilton Inquiry, for any of the Loyalist atrocities

that were committed south of the border.

Taoiseach Bertie Ahern TD announced on Sunday,

19th. December, 1999, that the outgoing Chief Justice, Mr. Liam Hamilton was

being invited to "undertake a thorough examination, involving fact finding

and assessment of all aspects of the Dublin, Monaghan and Dundalk bombings and

their sequel, including

Taoiseach Bertie Ahern TD announced on Sunday,

19th. December, 1999, that the outgoing Chief Justice, Mr. Liam Hamilton was

being invited to "undertake a thorough examination, involving fact finding

and assessment of all aspects of the Dublin, Monaghan and Dundalk bombings and

their sequel, including

- the facts, causes and

perpetrators of the bombings;

- the nature, adequacy and extent

of Garda investigations, including the adequacy of co-operation with and from

the relevant authorities in Northern Ireland and the adequacy of the handling

of scientific analyses of forensic evidence; and

- the reasons why no prosecution

took place, including whether and if so, by whom and to what extent the

investigations were impeded. . .".

This was the closest that the Dublin authorities

had come to acceding to the various family's' demands for a public inquiry in

those cases, but it remained to be seen if the formula laid out in Mr. Ahern's

statement was acceptable to all concerned.

Still,

the Ludlow family was mindful that their demand was for a genuine public

inquiry, and that now that the Northern Ireland DPP was no longer standing in

the way, there was no justification for Dublin's failure to convene such an

inquiry, perhaps on lines similar to those of the present British Saville

Inquiry into the Bloody Sunday in Derry.

One thing is clear though - the Seamus Ludlow

case was, at this stage at least, not even being considered by the Dublin

government for the Hamilton Inquiry.

Chief Justice Liam Hamilton was not being asked to look into the murder of

Seamus Ludlow and the subsequent cover-up and smear campaign that has been the

focus of the Ludlow family's campaign for truth and justice.

Therefore, the

Ludlow family circle's attitude to the proposed Hamilton inquiry was largely

irrelevant. The Ludlow family was given no choice to consider at the outset of

the Hamilton Inquiry, though it was

becoming increasingly clear that Hamilton could not produce the truth that was

demanded by the Ludlow family, and was perhaps designed to ensure that the full truth

of what was done would never be revealed.

The Ludlow family had every reason to believe

that the murder of Seamus Ludlow should at least have been included in Mr.

Ahern's inadequate proposals, however deficient they were when held up to close scrutiny.

After all, four Loyalists were arrested by the RUC for

questioning about that foul crime in February 1998; the Northern Ireland

Director of Public Prosecutions (DPP) had decided on 15 October 1999 that none

of the four prime suspects would be prosecuted; and the Ludlow family

had received firm information from within the Gardai that confirmed their worst

suspicions of an official cover-up.

Not least among their concerns was the

revelation of the existence of a long suppressed Garda file that contained the

names of several suspects. The file had been received from the RUC, in the North, in

1979.

The proposed private Hamilton inquiry did not satisfy the Ludlow family's demands, but at least it should initially have been an

option for the family to consider: to accept or to reject. By the summer of 2000

it was all too clear that Hamilton was indeed falling far short of the Ludlow family's

clear demands.

The family, through their solicitor, continued to demand the

holding of a full independent inquiry, where all necessary papers and witness

would be examined in public. Meanwhile, the private Hamilton Inquiry was going

nowhere, with expected dates for the conclusion of a first report not met -

effectively stringing out the whole inquiry into the bombings of Dublin and

Monaghan.

Matters worsened in October 2000 with the sudden and unexpected

resignation of Mr. Justice Hamilton, on, at that time unspecified, health grounds, before finishing his

report. Mr. Hamilton died soon afterwards on 29 November 2000.

Although he was soon replaced by

Mr Justice Henry Barron, it remained to be

seen whether or not the whole unsatisfactory process was being put back to

square one. Although the Ludlow family had rejected Mr. Hamilton's private

inquiry, this rejection was not a personal criticism of Mr. Hamilton himself.

There were strong indications by the end of January 2000

that the Department of Justice in Dublin was looking at adding the Seamus Ludlow

case to the late Mr. Justice Liam Hamilton's remit. The following statement from the

Private Secretary at the Minister's office comes from a letter, dated 31

January, 2000, to the Ludlow family's solicitor:

"The Minister believes that including the

case of the late Mr. Ludlow as part of the remit of Mr. Justice Hamilton would

be the most appropriate way to address the concerns which have been expressed

about this case. Accordingly, he has asked me to tell you that he is minded to

recommend to his colleagues in Government that the case be included in the

remit of Mr. Justice Hamilton."

The Department of Justice called upon the Ludlow

family's solicitor to inquire and inform the Minister of the Ludlow family's

attitude to this approach. As Mr. Justice Liam Hamilton was due to commence his

work very shortly, the Private Secretary said "it would be very much

appreciated if you could respond to the Minister's proposal within the next

week".

Notably absent from the Private Secretary's

letter was a response to the Ludlow family's repeated request for the releasing

of the recent Garda investigation report from the 1998 inquiry headed by Chief

Superintendent Ted Murphy, and other relevant files from 1976 and 1979.

If the Minister for Justice was expecting

immediate acceptance from the Ludlow family for a proposal that had neither been

made public nor explained in great detail at that time, he was to be disappointed. The Ludlow

family had not given up on its firm demands for a public inquiry and for access

to Garda and RUC reports on the sectarian murder of Seamus Ludlow. There were

still many questions to be examined before the Ludlow family could consider

giving assent

to the Minister's still private proposal for what was a private inquiry.

The then Hamilton Inquiry was not initially rejected

outright, but

the Ludlow family would require much more persuasion before they would accept

something less than their basic demands of truth and justice through a public

inquiry. Would the private Hamilton Inquiry satisfy all their demands?

Would it uncover

the whole truth about Seamus Ludlow's sectarian murder? Would it get to the

bottom of the RUC and Garda cover-up which has kept Seamus Ludlow's UDR and Red

Hand Commando killers immune from justice since 1976?

Was the private Hamilton Inquiry any more than a

last-ditch Dublin government attempt to control the release of relevant

information, to limit damaging revelations and to protect the image and

reputations of the Garda and others who may have serious questions to answer?

Was it a genuine attempt to uncover the whole truth regardless of the

consequence? Was it aimed only at bringing out the full unvarnished truth behind

the shameful failure to bring to justice those responsible for heinous crimes in

the Irish state? Would the various families be granted effective legal

representation, with the absolute right to demand the release of files and to

subpoena vital witnesses, who could be questioned under oath?

If the answers to these questions is

"No", then clearly the Hamilton Inquiry could surely not meet with the stated

requirements of the Ludlow family. If the answers to these questions is

"Yes", as Government statements seemed to say, then the

Ludlow family could ask, why not go the full distance and establish a

public inquiry? If there is truly nothing to hide, then there should be a public

inquiry.

On 25 February, 2000, the Ludlow family's

solicitor sent his response to the Minister for Justice, "reflecting the

view of the family in relation to the similarities between this case and that of

Pat Finucane". The solicitor referred to previous correspondence, saying

that he was looking "forward to hearing from you in relation to this matter

and in particular to receiving a copy of the Investigation Report."

The

solicitor concluded: "Again on behalf of the family we must emphasise the

view that the case for a public inquiry is compelling and unanswerable. We look

forward to hearing from you." The solicitor was still waiting more

than four months later.

The Ludlow

family rejected the proposal made by the Minister for Justice at a meeting with

him on 23 May 2001. By that time there was still no further progress and the

Minister remained controversially set against holding a public inquiry, although

he stressed that it was not ruled out for the future.

The Dublin government initially said that it

intended that

the then Hamilton inquiry will "have full access to all files and papers of

Government Departments and the Garda Siochana. The Government will also direct

that all members of the Public Service and the Garda Siochana extend their full

co-operation to him. Furthermore, the Taoiseach intends that the Government will

seek the co-operation of the British authorities with the Chief Justice's

examination.

"The results of the Chief Justice's

inquiry will be presented to the Government, and there will follow "an

examination of the report in public session by the "Joint Oireachtas Committee on Justice, Equality and Women's Rights or a sub-committee of that

Committee".

The following excerpt from the Statement by the

Taoiseach on the Dublin, Monaghan and Dundalk Bombings (19th December, 1999)

gives further details of the private process that the Minister for Justice had recommended to the Ludlow family, who remained opposed to this private alternative

to a public inquiry:

(Because of the separation of powers between

the Executive and the Legislature, it is not possible for the Government to

direct the Oireachtas or a Committee of it to take a particular action.

However, the Government would do everything in its power to ensure that the

Committee took this action and, as there is cross-party support for this

approach, the Government are confident that matters would unfold along the

lines envisaged.)

"It is also envisaged by the Government by

the Government that the Joint Oireachtas Committee on Justice, Equality and

Women's rights would direct that the report prepared by the Chief Justice be

submitted to the Committee, in order for it to advise the Oireachtas as to

what further action, if any, would be necessary to establish the truth of what

happened.

"The Committees of the Houses of the

Oireachtas (Compellability, Privileges and Immunity of Witnesses) Act, 1997

enables the Oireachtas to confer power on an Oireachtas Committee to send for

persons, papers and records and it is envisaged that these powers would be

invoked, including at the stage where the Committee, in public session,

considered the follow-up to be given to the report of the Chief Justice.

"The Government envisage that that this

consideration will involve hearings at which

- the

Justice for the Forgotten Group,

representing the injured and bereaved, would have the right to appear before,

and be heard before, the Committee;

- the Committee would exercise powers to direct

the material relevant to the findings of the report to be placed before it;

and

- it would also exercise powers to call persons

to appear before it to respond publicly to the report.

"As the Government see the matter, there

would be three approaches open to the Committee:

(i) advise that the report achieved as far as

possible the objective of finding out the truth and that no further action

would be required or fruitful;

(ii) advise that the report did not achieve the

objective which could only be done through a public inquiry; or

(iii) advise that the report did not achieve

the objective and the Committee or a sub-committee of the Committee should

examine the matter further (as outlined previously, the options available to

such committees or sub-committees include public hearings and powers to send

for persons, papers and records). . .".

It

was for the Justice for the Forgotten group

and the people bereaved and injured by the Dublin, Monaghan and Dundalk bombings

to decide whether or not the private Hamilton Inquiry process, as outlined above,

was

appropriate to their demands.

The Ludlow family

accepted their right to make

their own decisions in their own cases. The Ludlow family had considered

Mr. Ahern's and Mr. O'Donoghue's proposals for the Hamilton (Barron) Inquiry and

Joint Oireachtas Committee hearing and they were still rejected as having

no merit in meeting the family's stated demands.

The

idea of a public Joint Oireachtas Committee hearing had recently been severely

undermined by the gardai and the Department of Justice who had challenged its

powers in regard to its investigation of the controversial Abbeylara case -

making it little more than a rubber stamp body with none of the powers envisaged

originally by Taoiseach Bertie Ahern. It was daily becoming apparent that this

can be no alternative to a public inquiry as envisaged by the Ludlow family.

The Dublin Government's ideas for extending the

remit of the Hamilton (Barron) Inquiry so that it would look also at the murder of Seamus

Ludlow were outlined in further detail during Taoiseach's questions

in Leinster House, Dublin, on 23 May 2000. Mr. Ahern stated that this was

his government's advice to the Ludlow family, who he accepted have "strong

views and they are not yet satisfied that this is the best way to proceed".

Mr. Ahern repeated his previous claim that he

had

met with the Ludlow family. Well, this is strange news to the late Seamus

Ludlow's surviving brother, three sisters and many nephews and nieces and their

families, for no Ludlow family group has ever met with Mr. Ahern. Requests for a

meeting with Mr. Ahern have never been acknowledged. Repeated requests for such

a meeting have been ignored, while Mr Ahern has met with other families who have

lost loved ones in the North. To this day, no such meeting has ever been

arranged!

Mr. Ahern went on to introduce various arguments which could later be used as an

excuse

for any failure of such an inquiry. For instance, Mr. Ahern said:

"As Deputy Quinn is aware, there are

difficulties in the Seamus Ludlow case, including cross-jurisdictional issues.

An added complication is that identifiable individuals were accused publicly

in the case and the DPP in Northern Ireland, having considered evidence

available there, decided not to prefer charges. This will make a public

examination of the case difficult here. However, my view remains that an

examination by the former Chief Justice is the best way to proceed."

Such arguments promote little confidence that the

proposed Hamilton (now Barron) process will produce the desired results, or that it was ever

intended to. Certainly nothing

said by Mr. Ahern helped persuade the Ludlow family that Hamilton (Barron) was the best way

forward or any alternative to a public inquiry. The Taoiseach's position

was explained further in a letter to the Ludlow family solicitor of 28

July 2000. Interestingly, the Private Secretary's letter concluded:

"Under this approach, a public

judicial inquiry is not ruled out at this stage. It would be one of a number of

options that could be considered, following on the completion of an examination

by an eminent legal person.

"Nor would examination by Judge Hamilton preclude your clients continuing,

if they wished, to campaign for a public inquiry, as the Justice for the

Forgotten group continue to do in regard to the Dublin/Monaghan bombings.

"The case of the murder of Mr. Ludlow has been dealt with in a recent

submission to the Government. it is now expected that interdepartmental

consultations on the best approach will be brought to a conclusion soon, with a

view to a further submission to an early meeting of the Government."

Some useful points which will no doubt help guide

the Ludlow family towards a final decision were made by the broadcaster and

writer Don Mullan - noted author of the momentous Eyewitness Bloody Sunday

and the recently published book The

Dublin and Monaghan Bombings (published by Wolfhound Press,

October 2000) - in a communication with a member of the family.

Mr. Mullan, a valued

supporter of the Ludlow family's campaign for justice, has advised:

"There will, no doubt, be linkages,

especially regarding the perpetrators of the crimes and the collusion of

British State forces. However, I think it is important that we don't

allow the government to submerge all incidents in a pot of political stew.

Each crime deserves to be examined on its own merits. The dead and the

bereaved are entitled to no less.

"It is certainly worth considering whether or not you should cooperate

with a Hamilton Assessment of all the available evidence concerning Shamus's

murder and your subsequent experience with the Garda 'Investigation'.

Whatever you decide, however, I think it is important you insist on allowing

the Seamus Ludlow case to stand on its own, just as Dublin and Monaghan should

stand on its own, along with the Dundalk bombing and the 1972 Dublin

bombing.

"Having said that, I think it is very important that each individual

campaign should be united in a collective effort to support and encourage one

another."

Mr. Mullan has raised important points here. Can

an inquiry process dealing with more than one atrocity - the Dublin and Monaghan

bombings of 1974, the Dundalk bombing of 1975, and perhaps also the Castleblaney bombing

and other Dublin bombings as well as Seamus Ludlow's murder, treat each

case on its own merits or will it seek out simple common denominators and

thereby avoid close examination of the specifics of each case?

It is also important to the Ludlow family that

all others presently demanding truth and justice for other

Loyalist/British forces crimes in the Irish state, and their many other victims

north of the border, should collectively support each other. They are all

victims of state violence and their plight has been ignored by the very state

which has brought them grief and suffering. They all fully deserve the truth and

justice that the British authorities have long denied them and the Ludlow family

will support them in their just demands.

Postscript, 23 November 2001:

In

a devastating blow to the Dublin government's proposed plan for a private

inquiry and Joint Oireachtas Committee investigation into the 1976 murder of

Seamus Ludlow, the three-judge Irish High Court in Dublin, in a landmark

decision, has sharply restricted the scope of Oireachtas

investigations.

The Court

upheld a challenge by 36 members of

the Garda Emergency Response Unit against the conduct of the inquiry into the

April 2000 killing of John Carthy in Abbeylara, County Longford. Oireachtas

inquiries cannot now make "findings of fact or expressions of opinion"

which damage the good name of citizens who are not TDs or senators.

Further update: The Ludlow family met with the

then Irish Attorney General Michael McDowell on 21 February 2002 at Government

Buildings, Dublin. Accompanied by their legal advisor James McGuill, solicitor,

Dundalk, and, once again, by Jane Winter, Director, British Irish Rights Watch

(BIRW), London, the Ludlow family was informed that No Public Inquiry would take

place before a private Barron Inquiry with a Draft Terms

of Reference based closely on those described above for the Dublin and

Monaghan Bombings inquiry.

You

can read further about this setback for the Ludlow family's campaign for truth

and justice by reading the report that was published in the Dundalk

Democrat newspaper on 2 March 2002. In this, Jimmy Sharkey gives the Ludlow

family's first public reaction to the Dublin government's cruel decision to

continue with the cover-up.

The Dublin Government had decided to go ahead

with the private Barron inquiry, regardless of the Ludlow family's stated objections.

The Ludlow family restated their demand for a public inquiry and assured the

Attorney General that their opinion on the proposed private inquiry had not

changed since their unsatisfactory meeting in 2001 with the Minister for

Justice, John O'Donoghue.

However,

in June and July 2002, after much consideration, members of the Ludlow

family met with Mr Justice Henry Barron to assist him in his inquiry.

Though still calling for a public inquiry, the Ludlow family had been advised

that boycotting Mr Justice Barron's inquiry, which was going ahead anyway, would

not be a wise option at that time. The Ludlow family requested access to all

files and witness statements that were seen by Mr Justice Barron, but this

request was turned down.

The

Ludlow family met with Mr Justice Barron again on 14 November, and a list of

questions important to the Ludlow family was put to the judge. It was hoped that

the questions would help the judge and his private inquiry. Again, it was

put to him that the Ludlow family still requested access to files and evidence

that is available to his inquiry.

It

was hoped that such access would enable the Ludlow family to help the judge to

make progress with his inquiry. Given the Ludlow family's knowledge of the facts

of the case it was felt that they could help Mr Justice Barron, not least by

guiding him towards the relevant witnesses and assisting him with Ludlow family

comments on the evidence he sees and hears.

Unfortunately,

Mr Justice Barron did not agree to allowing such access to the Ludlow family.

However, he did agree to write to the Ludlow family's lawyer to indicate matters

that were raised in such interviews. This letter was to be passed to the Ludlow

family for their comments.

Mr

Justice Barron wrote the above mentioned letter on 27 February 2003. The letter

referred to matters that were raised at the previous meetings with Mr Justice

Barron, as well as statements made to him by unidentified witnesses.

Points raised by Mr Justice Barron included: